Don't miss your future favorite film!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the latest updates from the SIFF community delivered straight to your inbox.

Don't miss your future favorite film!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the latest updates from the SIFF community delivered straight to your inbox.

Tova Gannana | Wednesday, October 23, 2024

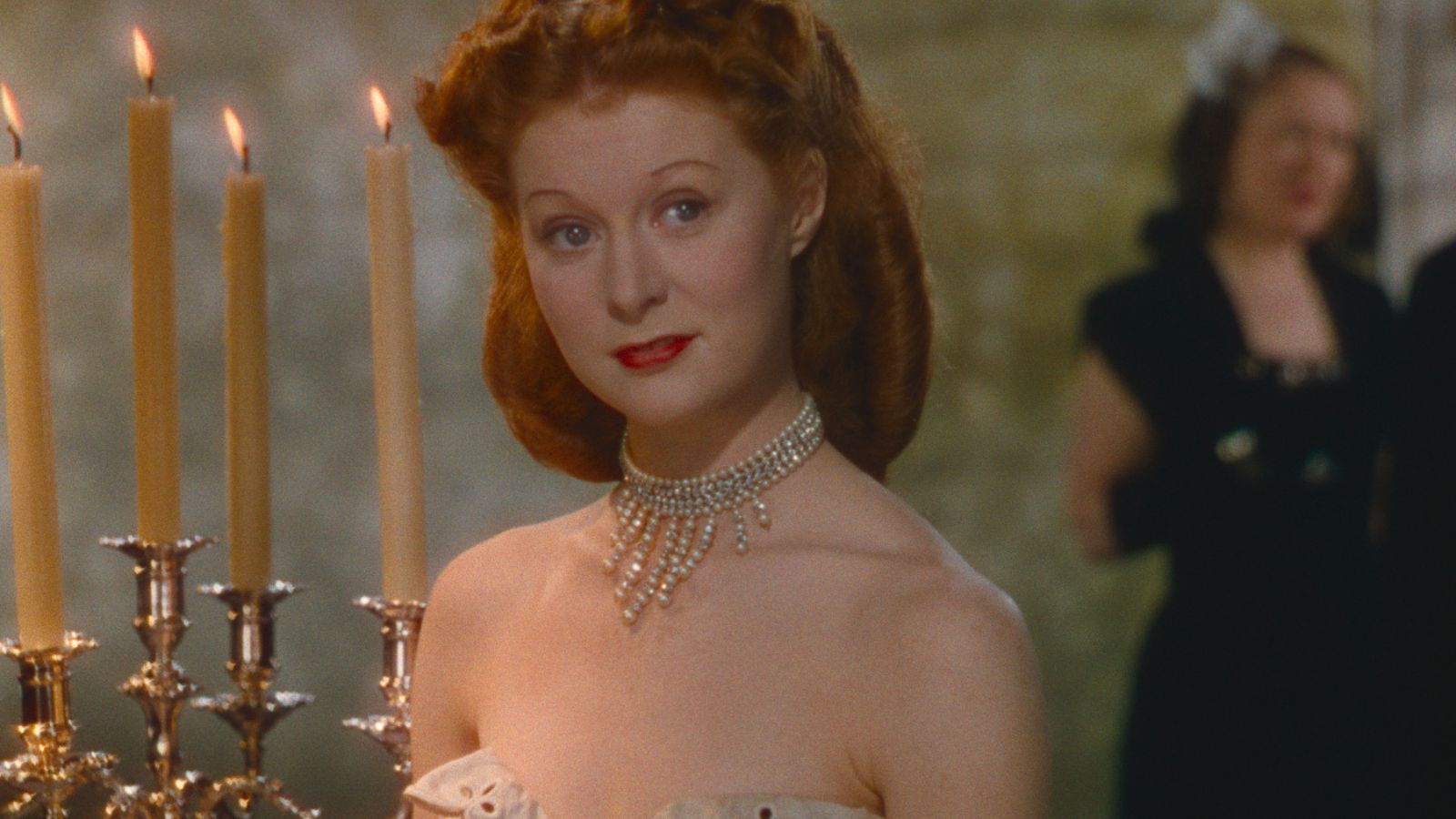

The Red Shoes (1948) film notes by Tova Gannana for our Enchanted Evenings: The Boundless Cinema of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger series, running September to November 2024 at SIFF Cinema Egyptian. Follow Tova on Instagram: @tovagannana

The series is presented by The British Film Institute, SIFF, and Greg Olson Productions. Passes and tickets available now.

Dance comes with music. To dance is to take a cue. Some are born dancers. Others claim two left feet. The beauty of watching someone move to a beat is like watching waves wash away at a beach: It seems to come naturally, like some kind of magic you are either touched by or passes over you.

Jack Cardiff, cinematographer of The Red Shoes (1947), said that the film was, “Half fairy tale and half reality.” A fairy tale is also a cautionary tale: Be careful what you wish for. Be cautious who you trust. There’s always a lesson.

Victoria Page (Moira Shearer) is a dancer who knows she wants to dance with The Ballet Lermentov. She knows this because she’s dancing with an inner direction. The impresario of the Ballet Lermentov, Boris Lermentov (Anton Walbrook), knows who he wants to dance for him. He thinks he knows what’s best for them. He wants his prima ballerina to be like a butterfly caught in a net: Not to harm her, but to keep her. He doesn’t want her to talk, fall in love, or get married, only to dance. He wears suits and dark glasses. His office in Monte Carlo has an arched window like the Ponte Vecchio. As the dance company goes home at night, one by one the dancers come to his door to say goodnight. They all call him “Boris”; Victoria calls him “Mr. Lermentov”. He calls her “Vicky”.

The Red Shoes is a dancers’ film: We don’t just hear the music; we feel the movement. The camera moves with the turns of the dancer; we see the audience from the vantage point of the stage. Behind the curtain there is panic, doubt, fear of missing one’s cue. Like all love stories, The Red Shoes is a tale of three. Julian Craster (Marius Goring), a young composer, also makes an impression on Lermentov and is hired the same day as Vicky. They join the Ballet Lermentov, and at first it isn’t harmonious between them: He is a composer and a conductor; she is a dancer. “The tempo is wrong. It’s too fast,” Vicky speaks out during rehearsal. “It’s the right tempo,” Craster snaps back. They’re youngsters in the company with much to prove. Passionate and talented, Craster ponders fame: “I wonder what it feels like to wake up one morning and find out one’s famous.” For Vicky, dancing is something else entirely. It’s her life’s motivation. It has nothing to do with fortune or fame. For Vicky, to dance is to be alive.

Lermentov and Craster insist with Vicky that the music comes first: “The music is all that matters, and nothing but the music,” Lermentov tells Vicky. “My music will pull you through,” Craster tells Vicky. They tell her this to boost her confidence. Like the spotlight, their words are meant to center her. They want her to think of the music as a tightrope that she either crosses or falls to the depths. When Craster and Vicky fall in love, the three of them fall apart: Their dance turns into dissonance.

Dance is all around us, but we’re not all dancers. Lermentov and Craster are believers, visionaries, in differing ways. “When you’re lifted into the air by your partner, my music will transform you,” Craster tells Vicky. "Into what?’" she wisely replies. He answers, “A flower swaying in the wind. A cloud drifting in the sky. A white bird flying.” He imagines, while she must feel. She’s his muse, while Lermentov wants to mold and keep her: “You cannot have it both ways. The dancer who relies on the doubtful comforts of human love will never be a great dancer. Never.” Lermontov is promising her a place as a great dancer, while Craster promises her his love for life. Why can’t she have both?

Ballet’s legendary choreographer George Balanchine said, “The mirror is not you. The mirror is you looking at yourself.” The Red Shoes is a mirror. We don’t have to be dancers to move to the music we hear. What are we passionate about? Unable to live without? Lermontov asks Vicky, “What do you want out of life? To live?” She answers, “To dance.” We know what a ballet is, but we use the word to describe illusion, an experience that goes smoothly, “Then again, it’s hard to match the high-wire feat of perfectly executed food served at perfectly timed intervals in restaurants where the ballet in the dining room belies the bedlam in the kitchen,” Frank Bruni wrote recently in the New York Times. This is the fairy tale; the reality is what happens backstage: chaos and magic, human beings in all their individuality, coming together.

The tale of The Red Shoes is one of getting too much too soon, of being taken advantage of, of greed, of jealousy, of desirability, of marketability, not on the part of Vicky, but of how she is seen. Lermontov wants what Vicky has. Vicky wants to dance. She has the heart for it, but not the stomach for the business of it. Craster loves Vicky, but lacks the imagination for how Vicky feels having given up dance to follow him. Both men want Vicky to be their ideal. Vicky follows the music. The red shoes she dons have power; they’re possessed. They have a direction that is inexhaustible, a dance with no end. But the red shoes, like Lermentov and Craster, are short-sighted: No one can dance forever; every dancer needs to rest. Every dancer needs another chance.

Don't miss your future favorite film!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the latest updates from the SIFF community delivered straight to your inbox.

Don't miss your future favorite film!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the latest updates from the SIFF community delivered straight to your inbox.